Home |

View all books

|

Bio |

Feedback |

Previous Novels

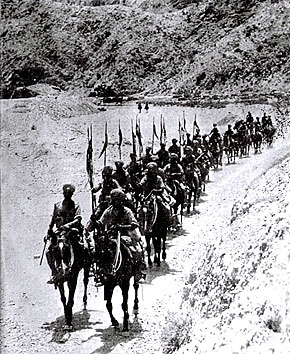

The

King's Gora-Wallahs

by

Don MacNaughton

Preface

This

is a

story of a

However,

above all else this is a story about the army in

This

book is dedicated to:

All

British soldiers who,

In

the 1920's and 1930's

Trooped

east by sea for service in the 'shiny'.

Men

known to the

Indian

native population as

'Gora-Wallahs'.

CHAPTER 1

There's little in my

lifetime left,

In the race I'm well

behind.

Still the memory of

my younger days,

So strong, so sweet,

so kind.

© Don MacNaughton

David

Kerr

Scant

attention was paid to the two old men as they slowly paced their way

upwards

out of the bowels of the

The younger but taller, Joe Penton, was seventy-eight, his hair un-thinned, silver white, with a trimmed matching moustache. Wearing a coat of thick, sand coloured camel-hair, in his right hand was a walking stick, used to ease the stride of his right leg, that years earlier, broken at the thigh by a Japanese bayonet thrust, was now affected by a touch of arthritis. Ben Tysall, his companion, aged eighty, walked with faint sagging of the shoulders, made more prominent by hands buried in his overcoat pocket but his back was held straight. Hidden by a grey plaid trilby was a casualty of the years, his once coal black hair gone, only a speckled, granite-toned lower fringe remaining.

It was almost ten o'clock on a mild Saturday evening in October 1982 and the two gentlemen were returning from what was for them a memorable occasion, the sixtieth anniversary of the sailing for India of the 2nd Battalion the Queen's Light Infantry. Memorable, because this was the last time it would be held. Every two or three years for the last twenty Lieutenant-General Sir Miles Holt-Bate would arrange for a formal regimental reunion dinner to be provided in one of the messes at the Duke of York's Territorial Army Centre, standing at the Chelsea end of the King's Road, London. Now it was being brought to an end for the most obvious reason. After sixty years, of the two thousand or so men who served with the 2nd QLI in India during the mid-1920's who qualified to attend, only seventeen had sat at that night's dinner. Of those hundreds of others who could not appear, most had been excused through fatal Indian service sickness, Pathan bullets, or later by Hitler's and Hirohito's bullets, mines and shells. It was for these who died as much as for the living that the reunion was launched. For, at the close of the meal, when General Holt-Bate bid everyone rise to their feet for the three loyal toasts: to Queen, Regiment and absent friends, it was the last that brought the diners' memories of distantly remembered brown, smiling boyish faces, framed in hot, dusty, sun blinding plains.

Of the two Joe had remained in the army longest: thirty-seven years, four of which he spent fighting the Japanese, first up out of Burma, then with the 14th Army back down again. He had finished in 1957 holding a quartermaster's commission as a lieutenant-colonel. Shortly after, during Ministry of Defence economy cut-backs, the Regiment was amalgamated, then in the 1960's amalgamated again. Today, the bones of what is left can be found somewhere in the framework of what is now the Light Division.

Ben

left

the army much earlier, in 1946. On

the

outbreak of World War II he was the Regimental Sergeant Major of the

1st

Battalion, who were sent to

Catching

the tube from

Ben Tysall, on the outside, seeing the mass of youths approaching, tried to drop back behind his friend to allow them free passage. Arrogantly ill-mannered with drink and numbers they shouldered past brushing Ben aside, one jabbing out with a straight arm to push him away. Ben, never in his life accepting violence meekly, struck out with a back-hander catching the youth on the ear with the heel of his hand.

"Imbecilic yob", dismissed Tysall, placing his hand back in his coat pocket to continue walking.

The skinhead who had received the cuff spun about holding his ear. Judging not the justification of the old man's retaliation or the cowardliness of his own actions, the young thug charged at Ben with kicks and punches, screaming abuse.

"See ya, ya decrepit old fart!"

The fist blow struck Tysall on the back of the neck. Turning, the second smashed his eye glasses to the ground, embedding splinters in his right eye first. With kicks being aimed at his crotch the old soldier stayed on his feet, doggedly but feebly returning punch for punch, then with the courage of the pack he was set upon and beaten to the ground by four or five gleeful skin headed creatures screaming foul abuse.

The speed of the action caught Joe totally unprepared. One moment his companion dropped back behind him, the next he turned to face a howling mob set on kicking his friend, now at his feet, to death. With an anguished bellow he lunged forward striking blows with his cane, beating back the mob to stand legs astride his fallen mate. Momentarily they recoiled, as much in shock of Penton's crazed appearance as from the sting of his stick. For crazed Joe was, so sudden and atrocious was the assault and so similar to a past attack on them, that he, in a raging trauma, was in mind and vision sped back in time, fighting that enemy and not these modern street savages around him.

Dusk on a Frontier hillside – it was Ben down this time – he defending him. The tribesmen in their ragged, grime-grey soiled dress were on them, jabbing and cutting with their curved bladed tulwars. Scraggy men with beak noses, unkempt beards and dirt tarnished turbans, they closed in. Again Penton smelled the stomach turning defilement of decayed, layered, unwashed body stench, amassed from goat droppings, wood and dung smoke, camel urine and a hundred other excreted wastes picked up while asleep on village earth. Wild eyed, he stood swinging his walking stick as if a rifle butt, his burning vow: they would not take his mate alive. Screaming almost forgotten eastern curses "Bug jow! Behnchod! Bug jow!" They, in his delusion, were also howling a Pathan battle cry: "Halla! Halla!"

Defending to his front, Penton never saw the brute who stepped up behind to plunge the blade of a knife into the base of his back. Sagging, he dropped his guard and was punched in the mouth. As his knees gave way a razor carpet knife sliced a thin, deep instantly bloody line from left forehead to jaw bone. Collapsed on top of Ben Tysall, a further attack with boots was delivered to his face and head. Then for several seconds the tunnel vibrated with victory whoops, cries and the echoing of fleeing boot steps.

Breaking the silence that followed came the click-clicking of a woman's high heeled shoes approaching from the tunnel's rail end. At first she believed them to be just a couple of passed-out drunks. Then she saw the blood, the little rivulets that joined to search for a way downward over the dirty cement floor and with a choked inwards gasp she stepped back, the sight of Joe Penton's gouged face almost causing her to faint.

--o0o--

The

nearby

On the fifth morning Penton, recovering from a second operation to ascertain mending to a kidney and intestines, stared at the ceiling with one eye, the one nearest the stitched slash. The other, swollen closed from repeated kicks, was an ugly distortion of dark purple and red flesh. He passed over an hour that way repeatedly closing the eye to rest it, slowly getting to grips with his memory as the effects of the operation's anaesthetic wore off.

"How is Ben?" were the first words from Joe Penton's lips on hearing someone walk past the foot of his bed.

"Oh, so we have decided to come back to the land of the living!" replied the black ward sister, who upon being asked, stopped to peer inquisitively into Joe's one good eye.

"I asked, how is Ben?" repeated Penton.

"Now, would that be Mister Tysall, Mister Penton?" answered the sister in a Caribbean accent, her voice a lilt going up and down as if on musical scales, presenting Joe with a question of her own.

"Yes, Ben Tysall, how is he?" pressed the old man once more.

"In better shape than you, Mister Penton" was the woman's quick return, "Now rest, keep quiet, the Doctor will be around soon".

As the ward sister took his wrist for a pulse check Joe again fell asleep.

By the end of the week both men were moved to a ward, confined to bed, unable to make contact and still far too ill to be allowed even to sit up. Here at least they were able to have visitors. Ben Tysall's granddaughter and her husband spent half an hour with him but she in the end left in tears. Penton's own granddaughter, his second eldest, came alone one evening, but on seeing him, collapsed on his chest to sob for most of her stay. She was his favourite because she reminded him so of his wife and Joe did his best to joke and comfort, stroking her hair.

Nine days after the assault, in the early hours of Monday morning, Joe Penton eased his bed clothes back, laboriously pushing himself upright to work his legs off the mattress and himself into a sitting position. Pausing to let the dizziness subside, he studied the glass panelled cubical three beds away. There the young duty night nurse was intent on writing a letter to her boyfriend. Preparing for his next move Joe took hold of the drip tube where it was fitted to a needle permanently fixed into a blood vein and taped to his left forearm. With a sharp tug he disconnected it, then clutching his bed, placed his feet on the floor to work his unsteady way around it. His neighbour, able to move about the ward with the aid of aluminium crutches, left these each night resting against a chair. Penton, taking one to use as a prop, painstakingly worked his way down the ward. Clinging first to a chair then pivoting on the crutch to grasp a table end, he slowly, with repeated stops for breath, navigated his way from bed to bed.

Halting at each of these he would study the occupant's face with his one good eye until he was sure it wasn't whom he was seeking. Then with a whispered sigh of recognition he shunted his body towards a bedside chair, guiding himself on wavering limbs into its rest. With a forehead speckled with tiny pearls of sweat, he slouched for a full minute to let the swirl and nausea confusing his mind subside and calm his accelerated heart beat. Reaching out to hold one of Ben Tysall's hands he gazed at his friend's stubbled unshaven face. From what he could see, which was just the lower half, he was in bad shape, swollen and scabbed. His eyes and head were tightly bandaged. What Penton didn't know was, under this, Tysall had a fractured skull, one eye blind from glass splinters, the other closed by puffy flesh and beneath the bed linen, ruptured organs. Adjusting his grip on Tysall's hand, Penton settled back in the chair in prelude to a vigil in the company of a man whose comradeship he valued more than his own life. Unexpectedly, the hand he held gave his own an exploratory press.

"That….. that you, Joe?"

Tysall's voice came slowly and artificially through a broken, wired-shut jaw.

"Yes, it's me," answered Penton just above a whisper, not wanting to alert the night nurse to the fact that he had gone walkabout.

"You alright?" asked Ben, his head motionless, only the lips moving.

"Like a Hindu temple gong," growled Penton dryly, "the only thing easing the pain is seeing you and knowing you must be hurting more".

This brought a gurgled chuckle followed by a pledge from the bedded man.

"Last time I get you into a fight, promise".

"When did I last hear that?" replied Penton with a half smile, his eye remaining closed.

"Ya! Ya!, remember the All India Football Cup?" Tysall's humour bubbling with the question.

"I remember the All India Football Cup," answered Penton in a deliberate tone, "why is it you always picked ten to one odds?"

Both laughed to themselves for a moment, squeezing the other's hand.

"Remember that march back through that bloody monsoon?" prompted Penton, continuing their drift back to youthful days.

"And the bloody CO on his bloody horse," confirmed Ben.

There followed a pause as memories wandered, broken first by the older man.

"Joe, remember Leela?"

"Of course" Penton affectionately answered as, softly, Tysall added simply, but in a manner that hung with emotion:

"I loved her Joe, I loved her so much."

Heedless

of

their injuries, disregarding the fact that they were wasting strength

vitally

needed to knit muscle fibre and hold together tissues that with the

ease of

parting cobwebs would begin to haemorrhage, they continued to jog, test

and

verify one another's memory of people, events, but above all places,

the names

of which were once as common to every English schoolboy as his own town

streets:

Gradually their reminiscences dwindled as did the speed of reply, Tysall's voice weakening, the hesitation between speech longer, until it was only Penton setting the questions. Then on asking, "That loose-wallah shot in the lines at Ferozepore, who shot him, Pani Waters or was it Bert Collins?"

From the man in bed no sound came, silent and serene he lay. Penton gave the hand he held a gentle squeeze. Tense with foreboding he waited for just the faintest of acknowledgements but none came. Penton, with head bowed, his eyes closed sank in his chair. As tears Joe knew nothing of trickled from his one good eye, his fingers took hold of Tysall's with a determined grip, the two wrinkled, thinly fleshed hands bonding.

His mind now at peace, his whole being perched on the edge of enchanted oblivion, Penton willingly let himself tumble over its abyss to fly to a land that had once made him plead and cry for release from its heats and depravities. But also, also to a land that noosed a man's soul with a silken cord, entwining each new sight and sound in retention, remaining in later years as fresh and clear as its first day of experiencing. Willingly enslaved, those hostages, would, in the stillness of a summer evening or the warmth of a winter room, hear again the rhythmical grind of the bullock cart, smell the sweetness of wild jasmine and see the kite hawks circle in slothful loops above a furnace dry plain.

High over a jewel blue ocean he soared, through the sentinel swallows stationed well seaward. At the boundary where the lands tart, pungent scent forewarned of its closeness, he sucked in the familiar breath.

"I've returned," he almost cried. "I've returned."

At

its palm

fringed shore he climbed above the coastal Ghats, over the cane and

millet crop

fields of the Deccan plateau, to green wooded hills and thick

foreshadowing

jungle. This gave way for many miles to withered land, once sprouting,

and now

dehydrated life gravely awaiting the monsoon rains. Now border green

appeared

along the banks of the Ganges, the life and mother of

To

his

right the tea plantations of

"A kiss?" she was saying, "a kiss for saving my life? I'll not pay a forfeit for that."

Then she tripped away to the edge of a sloping glade to turn about. Beyond was a broad valley that plunged downwards five thousand feet to a river, silver thread in size. Way off in the distance were purple mountains, their crowns all smothered in grey banks of rain filled murk, except for one protruding out to catch the sun's full blaze, its snowy greatness floating as an island on cotton white clouds. Separate from all else, this, the grandeur that was Mount Everest. Flanking the glade were evergreen Rhododendrons, bloomed in reds and pinks, again the fragrance of pine and wild roses adding to the delight of the moment.

Standing with arms at her sides, the girl, with a challenging smile, set her terms:

"A kiss as a forfeit I'll not give you, Joe Penton. What I will do is give it as a gift in gratitude. But you will have to come and claim it!"

As her arms swung out from her body, palms opening to beckon, the smile faded to one of languor, filled with enticement.

"Come Joe, claim your reward."

This time he did not rush, not like the first time – there was no need. They were here together once again and this time, this time they would not part. Spreading his own arms, with an unhurried lightness of pace, he began to approach.

"I'm coming Rose, I'm coming."

CHAPTER 2

The adventurer is an

outlaw.

Adventure must start

with

running away from

home.

William Bolitho

The last item Joe Penton picked up to stow in his small hand-case, was his father's present, given to him the evening before. Lifting the sparkling brass safety razor from its small wooden container box, he admired the instrument's newness, then replacing it, closed the little lid, securing the locking catch. The present was a combined gift marking two occasions: his eighteenth birthday and his departure from home. Joe was off to join the army.

Born

in the

next bedroom but one, he had grown up in this house, a house on his

father's

four hundred acre tenant farm. The home and farm, owned by a Lord,

whose family

claim dated back to William the Conqueror, was only one of several such

holdings

on the estate. Both

building and land

came together as a farm more than a century earlier, when the crops

taken then

were mostly root and cereal. However, this being the

Leaving his bedroom, Joe descended the stairs to say his first goodbye. His mother was in the wash-yard behind the kitchen, taking a linen sheet, just hand washed on a scrubbing board, from a large, soap-filled copper basin. She was in the process of wringing it through a hand mangle with wooden rollers, before rinsing it in a tub of cold water.

"We're all ready for the off, then?" she asked, looking up on hearing his metal heeled boots scraping on the flag-stones.

"In a moment," answered Joe uneasily, finding the ceremony of a formal goodbye uncomfortable.

His

mother,

aware of this, immediately defrosted the air with a smile. Drying her

hands on

her house-work apron she brushed a lock of speckled grey hair back into

place.

Taking an arm she walked him through the house, reminding him that from

time to

time a letter would be appreciated. At the gate they said their

farewells with

a hug and kisses on cheeks, tears kept in check. His mother, a farmer's

wife

with daily chores of her own, did not linger over his departure; a

minute to

wave her son down the farm lane then it was back to the washing. Now

past

The third time Joe turned to wave, his mother was gone.

To his left, within the huge brick and timbered barn with its weathered grey thatched roof, was where Joe had first realised he would have to find himself another life other than one on this farm. It was at the annual harvest supper held each September, given as a banquet by his father, to show his gratitude to the farm's workforce for their service throughout the past year. With the barn cleared, tables were laid and oil lamps hung from beams to give light in the windowless chamber. At the top table his father sat with George Peters, his foreman and James, his elder brother. Down the arms of this U-shaped dining formation, tucking into legs of ham, roasts of beef, pork and lamb, were the rest of the farm staff: carters; dairymen; water-keepers; groom-gardener; farm hands; game keeper; his under keepers who managed the ferrets and young sons who worked for the farm, subordinate to their fathers. It was when the foreman got up to reply to his father's seasonal speech, that Joe first ascertained a fact bearing directly upon his future. In previous years he would have begun by addressing a thank you on behalf of all the farm workers to his father, the 'governor', but this time he also included 'young master James'. James was twenty and had attended agricultural school. This simple act of innocent politeness, at first to Joe, seemed nothing but in following days it kept springing back to mind, until its significance flowered the fruit of truth. James was to be the heir and on his father's relinquishing tenancy of the farm, it was to him that it would, no doubt, first be offered. By Michaelmas, the farmers' New Year, only a few weeks later, Joe had made up his mind, his life's purpose could not lie with this farm and set his fate, he would leave before the spring.

A

short

distance on, where the leafless plum trees that lined the farm lane

ended, were

the dairy cow sheds. In

the yard old Tom

Fern, the head dairyman, was loading the farm's horse drawn wagon with

the

previous evening's and that morning's milk. From the dairy cool-room he

and two

of his milkers were lifting the silver metal churns from the loading

platform

into the well of the wagon. Nelson and

Raising an arm, Joe called to the grey bearded man jinking his milk containers into a neat pack.

"Tom! I'm just up to the West Hill rick to say goodbye to the Governor. But I'll not cause you to be late".

Thus confirming his lift to the train station.

"There's no need to rush, Master Joe. I be waiting at gate when thee done," answered the dairyman, endorsing his reply with a wave of a bony hand.

A ten minute hike brought Joe to the farm's main centre of work for that day. On the brow of a round topped field a gang of men under the watchful eye of his father were threshing a corn rick of barley. The thresher was powered by a steam engine and the two men who ran it had left their beds at four that morning to have the engine ready in place for the commencement of work at seven. It was a dry, cold morning in early March 1922 and late for threshing, but with the sudden jump in the price of feed stocks Joe's father, rather than market the grain, intended its use to supplement the dairy's cow feed.

Threshing was a team job that could not be interrupted. Once begun, the whole procedure must, for the economics of labour, flow with the rhythm of a carousel. As the sheaves were forked up to a man on the thresher, their binding string was cut and the headed stalks fed into the machine. Below, others gathered the grain and built a separate rick from the rebounded chaff. So Joe had picked his moment to call - it was half past nine now and the team was just breaking for their lunch.

For five minutes this group of comrades, because he, since a lad, had shared their work, plied him with good-natured ribbing and well wishes, their faces and clothes caked in grain dust, for threshing was a filthy chore, having to work constantly smothered in its powdery soot.

"You gie' the NCO's no back lip!"

"And jist mind what they say. Doan't want the caper they cause thee for not.

This from two grinning ex-soldiers, survivors of the Great War.

His father, before mounting the pony-drawn trap he used to tour the farm, took Joe's hand, wishing him God's good fortune with the army. Then with a click of his tongue to the horse, he sped off to fulfil an inspection appointment, accompanying his head water-keeper over one of the down river meadows.

Their parting, as with his mother, was not one edged with emotion. His presence by them would be missed, as he of theirs but his parents were of seasoned farming stock and well recognised the logic behind Joe's leaving. A tenant farm could not be halved nor was it in his father's power to do so; Joe was merely treading a path already well travelled in past centuries by countless younger sons. Turning his face from the receding outline of pony and trap as his father trotted the rig into the field's first dip; he waved a last cheerio to the team of threshers eating their cold lunch.

For some moments the youth, on walking away, struggled with the comprehension of his action, but on seeing Tom Fern hunched on the dairy wagon waiting at the farm's boundary gate, he broke into a trot, all doubt vanished.

--o0o--

Joe

Penton

had never been to

Coal, in unlimited abundance, was the country's fuel and had been for numerous decades, but unfortunately its widespread use had a price: The day, dull and cool in the farm lands of Kent, was here thick with artificial haze, the air itself so odious with acrid fumes Penton could taste the atmosphere to the same degree as he could smell it, which, to a visitor, was not a difficulty. Surrounding him were street after street of high buildings, business as well as domestic, and should have stood out in rusty, house-brick red, edged with pleasant, light coloured sandstone or ash white marble facing. Instead, every surface was coated in black soot that lay like a funeral shroud draping the entire city. The cause was not a mystery. Jutting above every roof were uncountable chimneys crowned with tall, slender decorative pots that oozed constant ribbons of blue grey smoke.

Fetching a leaf of paper from his coat pocket, Joe studied a rough street sketch given him by one of the farm-hands, who knew where the nearest army recruiting office was. At his elbow a man in his late twenties, one-armed and with an eye patch, sold papers, the headlines of all proclaiming the previous day's joyous event of the royal wedding between Princess Mary and Viscount Lascelles. Joe fleetingly considered confirming his direction with this man but then thought better. Obviously marked by disfiguring tokens of the Kaiser's War this was not a person from whom to request information about joining the army.

Setting off, he walked along the main street. Up on the walls of some of the buildings were advertising bill boards praising the attractions of teas, whiskeys, tobaccos, gravy stocks and many other commodities. Halting on one corner he again checked his sketch. Down the cobbled side street a horse-drawn coal wagon was being slowly led by a young boy. In front a man, clothes, face and hands stained with coal-dust, paced lagging steps while calling up at the tall tenements: "Coal! Coal!" As Joe watched a woman appeared, pushing a coin into his hand. Tipping his cap to her, the man hoisted a coal bag from the wagon onto his back, before following the woman into one of the buildings.

Penton found the recruitment office twenty minutes later, after first interrupting his search to have a light lunch at a tea shop. The cost: tuppence for a hot bun and a penny for tea.

Next to a branch office of the Abbey Wood Building Society, he spied a soldier standing on doorway steps. Beside the steps was a framed poster extolling the joys of enlistment.

"I've come to join," announced Penton politely. "Who do I see?"

"Army's

full up. Try the navy,

Joe, shocked speechless, could only gawk.

The soldier, in black boots, high puttees, khaki trousers, jacket, peaked cap and red sash angled across his chest, stood hands behind his back, rocking on heels, eyes engrossed in something across the street. Joe, his heart sunk to his feet, froze with indecision to the spot while the soldier, waxed moustache, hair sheared so close none was visible below the cap, totally ignored the youth. With his plans in ruins Joe turned about, shoulders sagging, to walk away.

"Here now, lad, let's not be too hasty with the feet. Perhaps we can find something to suit your talent," called the soldier. "You weren't planning on being a jockey, were you?"

"Jockey?" echoed Penton, mystified.

"Cavalry, my cocker, Cavalry," deciphered the man in uniform.

"No,

No,

mister! It was my

"It's sergeant my boy, not mister," pointed out the recruiter, bringing his hands from behind his back to lay a finger on three stripes on his sleeve. In the other hand was a board with a sheet of paper clipped to it. This he began to consult.

"Let's see now". He began running a finger down the paper.

"

"Yes, that'll do fine." Joe leaped from the depth of his despair like a trout to a fly hook.

"Well come along in then, and we'll deal with the formalities," suggested the sergeant.

Inside, business was done in a broad hallway from two desks at the far end, office doors were spaced along one side, a row of chairs along the other. Asked his age and a few other simple questions Joe was handed a shilling coin, told to sign his name, then ordered to take a chair and wait. He picked one unoccupied, next to a dark, square shouldered man in a rolled woollen cap and a heavy sea jacket. His face was weather beaten but Joe put his age at not much older than himself.

"Smoke?" offered the stranger holding out a packet of Churchman's Tenor cigarettes.

"Ben Tysall," he introduced himself, after lighting one for himself. Penton declined while making his own name known.

"What mob you given?" he asked exhaling his first breath of smoke.

"Oh…..

"Queen's Light Infantry," helped Tysall with a smile. "Ya! Me too. I asked for my old Regiment but then let him convince me I'd be better off signing for the Queen's."

Joe, bracing up at hearing Tysall say he had done previous service, was forestalled in learning more by him leaning forward to beckon a tall, skinny, red haired youth to him. He, leaving one of the desks, was on his way out, crestfallen.

"What's the misery, Bluey, get yourself turned down?"

"Eh…. Oh…. Ya! Right and proper too" replied the youngster bitterly.

"Why, what's your affliction?" pressed Ben.

"Age." confessed the youth sheepishly, "Got caught unexpected like, when the bloke asked me how old I was, told him the truth, fifteen."

Ben, forearms on knees, hands cupping his cigarette, his voice low but firm, gave a gentle order: "Get about, march straight back to the same fella' and tell him you're eighteen".

The red haired youth didn't move, still doubtful.

"No hawing," encouraged Tysall, "besides, what's to lose? Now back you go".

With a half sigh the young man raised his head to step about and present himself in front of the same desk as before.

The sergeant sat there, a different man to the one who enrolled Penton, watched his second arrival.

"Well, fellow me lad, what's it this time?"

"Please sir, I'm eighteen," lied the youth with all the conviction of a mouse.

"Grandly stated my boy." congratulated the sergeant, thrusting out both arms, a coin in one hand an ink pen in the other. Here's your King's shilling, sign your name."

Shortly after, the three newly enlisted recruits were approached by a third sergeant and told that they, under his escort, would now journey across to another part of the city for a medical and if passed, be sworn in. Joe, following Tysall, who was carrying a drawstring kit bag over one shoulder, out of the main door, tripped suddenly on the first step on overhearing the conversation between a youth on the street and his recruiting sergeant, again studying the shops opposite from his steps.

"Looking to join the Queen's Light Infantry" said the youth.

"You've no chance there, my hopeful friend, how about the Royal West Kent's? We've a vacancy or two with them."

It seemed at least one recruiting sergeant had found a way of spicing the tedium of his daily task.

Boarding

a

tram, they were taken to and led down into a tube station. The

underground rail

system that ran like a gigantic rabbit warren below the heart of one of

the

world's largest metropolises was for Joe Penton a remarkable

revelation. The

deep descent, the crowded platforms, the rush of air preceding the tube

train's

arrival that had both men and women steadying their hats, and the

quickness of

the journey, left him only taking in half of what had gone on. Emerging

again

into the blunted city light the little party found their destination to

be the

"Sergeant-Major," he addressed another upright, moustached soldier who accompanied him into the hallway; "we must make an effort to get some of these people away before tea time."

"Very good, sir," answered the sergeant-major, "I'll form them up into railway station parties and despatch them."

Very soon after the sergeant-major returned with a small knot of sergeants.

"Now listen in all of you. It's time you gentlemen were elsewhere". The sergeant-major's voice, raising two or three decibels captured and held everyone's attention.

"When I read your name out, stand up and be prepared to follow after one of my sergeants."

From

a

sheet of paper he called out five names before handing it to a sergeant

with a

cryptic: "Royal Fusiliers, Hounslow and East Surrey,

Waiting

for

that party to leave he began calling names again, finishing with

another

hand-over of paper to a second sergeant. "King's Royal Rifles,

On Penton and Tysall with two others being called to their feet, the sergeant-major's directive to their sergeant escort was: "QLI, Harwich".

After

a

tram ride to

Amid

a

chorus of neighbouring whistle toots, witches' hisses of steam and

grinding

metal wheels, their own engine, snatching its carriages in impatient

jerks,

began the scheduled journey to the

Sid Firth, eighteen, stocky with dark hair combed straight back, a broad neck and thick waist, his face blemished with spots and pitted from a childhood illness, also kept his life history brief. From Bethnal Green, he had worked for the last two years for a firm of furniture repairers. What he didn't divulge was that his father, a drunkard, had remarried after the death of his wife. The stepmother, a widow with a family of her own, which she cared for at Sid's expense, provided him with the final spur to get away.

Fortunately,

after relating the dullness of their rise to adulthood these three were

able to

listen the miles away through Ben Tysall's lively escapades. At

fourteen he had

lied his way into the army, spending almost two years in the trenches.

On

de-mobilisation he took to the sea as a deckhand only to sign off his

ship in

Recounting

this period of his life in open conversation was something Ben could do

with

ease but there was a dark childhood he kept secret, allowing very few

throughout his life to know of it. Born in a

Separated from his sisters Ben found himself in a brutally run orphanage until the age of twelve. At that point the war began to draw men away from most semi-skilled employment, which gained him his release. For two years he worked as a butcher's mate, his wages so eaten away in payment for his meals and lodgings, a small dim, stuffy room above the butcher's shop, that he rarely had enough for a hot currant bun at night. Finally, fed up with the long working hours, of wearing others' cast off clothes and with the ill-tempered behaviour of his employer, after a bitterly cold December night in 1916 that had kept him awake throughout, Ben ran off to join the army.

At Harwich station forbearance was required. When the guard did turn up to unlock them, it was in the company of a stout, khaki uniformed private soldier in a leather jerkin.

"There

we

are

"My, don't these red arses ever get different? – same 'ellish innocent faces." Not expecting an answer he turned away with a motion for them to follow. But his old soldier's comment did prompt a reply from Ben Tysall:

"OK lads, pick up your gear and tag along with that geyser with the big belly and mouth to match".

The stout soldier heard this but only half looked back over his shoulder, before pointing at a cluster of crates and jute gunny bags.

"Right, grab a'hold of them here quartermaster's stores and put them aboard the transport."

Looking in the direction of the soldier's nod, Ben saw what he recognised as an army GS wagon hitched to a team of horses. Manhandling the goods in three trips they were stowed in the cargo well, then with the four new arrivals sitting on top, they set off, the wagon's steel rimmed wheels grating on the cobble stones, the horse shoes tapping out a metallic hornpipe.

Because

of

the overcast the evening twilight was racing to full darkness, but not

so that

Ben didn't realise where they were headed. Well outside the town on

what used

to be a broad rolling pasture, was a large hutted encampment. He

remembered it

as the camp to where he in 1919 returned from

At that time, with so many leaving, small batches of young recruits were also arriving. They, targets for the mobs, who would charge drunkenly into their accommodation turning beds over and threatening them, were so desperately needed for the army of occupation in Germany that the training staff would fit them out with uniforms, take them out for the odd stroll around the local lanes, then without so much as firing a rifle, ship them off to police the occupied Hun.

Entering the main gate a painted sign with a regimental crest could just be read in the fading light: Training Depot, the Queen's Light Infantry. After being made to unload the freight at the quartermaster's stores, a corporal took charge of them, issuing bedding, eating utensils and an enamel mug and plate. Taken to one of the huts occupied by twenty beds and ten other men, some of whom were like themselves in civilian dress, all eating off tabled forms, they were told by one of the uniformed eaters to claim a bed. He, without a jacket, showing braces over a collarless grey shirt, introduced himself as the hut lance-corporal, also chasing a man off to collect a late helping of grub and tea, both arriving in pails.

After eating and washing their plates and mugs in a washroom sparsely equipped with tin wash bowls on slate slab decking, water from cold caps, and open drains, the corporal gave the late arrivals their introductory chat. He warned that next morning their civilian clothes would be taken off them, an issue of army kit given and that all was to be cleaned, hung on pegs above their beds, and placed on display or out of sight in a kit box. Next he gave a hurried demonstration of how to arrange the bed for sleeping.

This was in two halves, an iron frame with interwoven metal struts and pushed one into the other to gain more space during the day. Once assembled, the mattress was laid out: three coconut-hair filled hassock type cushion pads, referred to as biscuits. The sheets, yellowish, were starch stiff, giving the sensation when used, of slumbering in a paper bag, while the blankets wreaked a musky smell from neglect in storage. With 'bedding in' completed, the lance-corporal left these latest additions to the regiment to their own entertainment, giving light warning of when they would be next required.

"Mind you sleep like angels tonight, tomorrow will be a perishing busy one."

"Here, Joe, let's you and me have a nose around" suggested Tysall, springing off the bed he had just made.

Outside, Ben navigated through the camp area as if he was seeking something out. The huts, wooden with slate roofs were pathway-ed between with wooden duckboards. Where there were none, walking boots and winter rain had combined to manufacture mud, but only in the occupied portion of the huttings, which was about a tenth of the buildings. The remainder, once a city of troops, now lay derelict through inattention and indifference, the oncoming knee high spring grass soon to turn each hut into an island.

"Yup, here's the one," said Ben, bringing both to a halt.

Treading between the disused ghostly buildings Joe found himself making out in the evening dark nothing more of significance than two rows of concrete foundation supports, interspaced among half overgrown blackened timbers.

"Here's what?" he asked.

"Headquarters

hut," answered Ben, showing a smile. "Or what's left of it. I burned it

down in

'nineteen. Well!!! Me and about two hundred others. Just back from

Nostalgia quenched, Ben now set his goal on finding a drink. This he would like to have been a pint of brown ale but had to suffice with a mug of tea and a cake at the Church of England Institute hut.

Returning to their billet, the night air, turned chilly, drove them both to close initially around the iron coal stove in the centre of the room. Activity elsewhere centred mostly on brushing, polishing or squaring up by those who had drawn their issue of kit. At one end of the hut though, a card school was in progress, being played off the top of a wooden soldier box near their beds. Both Joe and Ben, with nothing better on show, sat back watching the hands being played. The game was poker with five people taking part, one, Tommy Gilbert, who was not having much luck. In fact he had never gambled before and had only reluctantly joined in on the insistence of the two men who were winning. Tommy had begun the game with eight shillings and five pence, all the money he had. On the box lid in front of him remained only two and nine.

"That's another to me," sounded a burly youth with pale skin, his dark hair parted in the middle. Triumphantly he laid his winning hand down to rake the small cluster of coins towards himself, leaving a penny behind. "There's me in. Come along now! Dub up! Dub up!"

The others added their own penny to the centre of the box, staking their claim to cards for the next hand, except Gilbert, he hesitated.

"Come on, chum" urged another of the players, a mate of the first, tall with long arms, rust blond hair, his face lengthy with a square jaw. These two were the ones doing all the winning.

"I don't know." pondered Tommy, "I think I've had enough".

''Ere, you don't want to do that," advised the darker one, flashing a smile but not from the eyes.

"Luck takes funny twists, pull out now and you could miss a couple of winning hands."

"Aye, that's the way of it. Keep your seat and make a fortune," added the taller.

Not enthusiastically Gilbert played the next hand and again lost. Unprepared to risk more of his meagre wealth he began to pick up his few remaining coins, making an apology for not getting the hang of the game and having to withdraw.

"Nay! Nay! Chum, you're too hasty". The darker player placing a hand on Gilbert's shoulder restrained him as he made to get up.

"No! No! I can't afford to lose any more," replied Tommy, pleading.

"Look now, you'll start on a winning run I can feel it coming. Now sit down". The hand forced Gilbert back onto the bedside.

"The lad said he's had enough," raised an authoritative voice, clear and raw.

In dead silence all heads turned to Ben Tysall resting back on his bed, one elbow propping him up, both hands clasped.

"Who asked you to stick your paddle in?" questioned the dark youth, his words vinegary.

"It's not good practice to start out in life in the army by fleecing blokes at cards who well might be watching your back in a tussle where bayonets are flashin' about."

"Fleecing?" the word was spoken by the card player as if a sharp question.

"That's a fact. Haven't seen a hand go to anyone but you and your mate since I been sat here" pointed out Ben dryly. The dark player rose to his feet challenging, "Don't much like being called a cheat".

Tysall as if with glee leapt to his feet to draw with one toe, an imaginary line across the hut floor. "If that's a serious thought chum, then step across this line and we'll settle the error".

At this the taller of the two also stood. "Let's give him his go, Danny".

"So we want to play in pairs do we?" defied Ben with a wolfish grin and a voice that sounded almost happy, "well if that's the dance then me old mate here will be more than delighted to square the empty corner."

Joe

Penton

who had sat and watched the drama unfold found Tysall's indicating hand

centering

on his chest. Face shocked blank, the

"Come along, beauty; put your toe on the mark".

Ben, standing on his line, swept a hand over his black wavy hair before spitting into both, then waited, his fists turning circles at his waist.

"Go on, Danny, give him a good biffing," encouraged the tall card player.

Danny stepping forward, squared up to Tysall with a boxing stance. For several seconds neither made an attack, then Danny lashed out with a right swing. Ben, skipping back, waited as he twisted to recover, planting two low punches, a left to the ribs and a right in the solar plexus then as arms instinctively dropped, set a cracking straight right into a side jaw. Danny, his head snapping back, sprawled sideways and down, out unconscious.

"OK chum, your turn next. What they call you?" Tysall not taking a breath beckoned the tall, rust blond youth forward.

"Been answering to Ginger most me life". The reply was gruff and his look, after a slow observance of his unconscious partner, smouldered revenge.

"Well, this here is Joe Penton," introduced Tysall, slapping Joe on the shoulder as he stepped up to the mark.

Penton had never engaged in a real fist fight in his life. He and his brother had often shadow boxed in the hay loft of the barn but a bare knuckle brawl, never. Facing up to each other, Joe his fists high before him in the traditional style, Ginger's down at his waist swinging back and forth, both waited for the other to make the first thrust. This very soon was Penton, face firm but his sky grey eyes betraying foreboding. His swing to the other's head rounded short of its target with Ginger jerking his upper body back before instinctively countering with a punch to Joe's own head. Landing on the bare boarding floor between two cots, he felt pain and a nauseous sickness and didn't like it. On his knees regaining himself he tossed his head to clear the blond hair from his eyes, looking up at an opponent strutting with the assurance of a farmyard cock. Bounding to his feet, Penton flew at him throwing repeated wild punches. It was no longer a dispute settling boxing bout, just a melee of thrown fists and tangled arms.

At five foot eleven Joe was still the shorter man, Ginger being two or three inches taller and he had the longer reach, but Penton was the stronger and he was mad. Punches struck and received gave each his turn on the floor, sometimes together. This rest though, was brief, for a crowd had gathered around cheering encouraging, readily assisting both combatants to their feet again. Its conclusion when arriving was swift and instant.

"Hell's pit you lot!" The hut lance-corporal, off for a short visit to a pub below the camp had returned, his shout bringing stillness to the room.

"Leave you unwatched for five minutes and you're knocking the starch out of each other".

"Not that at all, Corporal," declared Ben Tysall with earnest conviction. "An exhibition of boxing prowess. It's just that Joe and Ginger here, being a bit weak on the fundamental skills looked a might un-gentlemanly".

"That a fact?" doubted the lance-corporal, spying loose cards on the floor. "Well next time the urge manifests we will do it like gentlemen, down at the gymnasium, with proper gloves on."

Then instructing Penton and Ginger to shake hands, he hurried them off to the ablutions to wash away blood.

"Now the rest of you," he commanded turning on the room, "get tidied away and into your beds. The duty bugler will be blowing lights out shortly and tomorrow morning I'll expect you all up before bird twitch".

Long after the bugler's notes had faded and the room darkened, Joe Penton lay awake reflecting on the day and its bruising conclusion. If at home, he would have ended the day, climbing the stairs to his room with an evening glass of the farm's dairy milk, heated by his mother. Instead here he lay, carefully resting the back of his head on a sack hard pillow, his face discoloured and throbbing with pain.

CHAPTER 3

Beware of all

enterprises

That require new

clothes.

Henry

David Thoreau

"Battalion, a---tten---shun!"

Regimental Sergeant Major John Rickman, standing rigidly to attention, his eyes hidden beneath the broad brim of his Wolseley topee swept left and right hunting out movement among the nine hundred men ranked by companies before him. Detecting not a flutter he turned sharply about to report to the adjutant that the battalion was present and correct. At this, given a, "Very good Mister Rickman. The battalion may stand easy," he again twisted about his upper body, not altering one degree off the vertical.

"Battalion --- stand at --- ease." As nine hundred iron shod boots crashed as one, the echo of it sounding off ships' sides and coughing back from shed interiors, stiffly fixed limbs answered a second command to relax. "Stand easy".

Joe

Penton,

stationed in the front rank of 6 Platoon, B Company stretched his back

as his

head turned, taking in the surroundings. It was nearing

Throughout

the whole of their six months training no secret was made of the fact

that

every member of Penton's recruit platoon were earmarked for the 1st

Battalion

stationed at Jersey in the Channel Isles and shortly to return to

Catterick

Camp. Not until the very last minute, just after returning from their

ten days

leave on completing recruit training did they find their destination

changed to

the 2nd Battalion at Aldershot, under orders for

The

Queen's

Light Infantry began life in 1759 as the Queen's Regiment of

Volunteers, raised

among county towns and villages south of

On

the

conclusion of the Great War and the mass disbandment that followed, the

QLI, as

did the rest of the army, wiped most of their emergency formed

battalions off

their rolls, most that is but not as many as the government would have

liked. On the

cessation of hostilities

with the Central European powers, containment of Bolshevik Russia,

occupation

of the conquered and the troubles in

In

the case

of the QLI this meant further reductions, and retirement. On

Free to wander around the troops' rear half of the ship, a knot of 6 platoon with nothing better to do watched as the officers and married dependants of the battalion filtered aboard their forward half of the ship.

"Here, Jeff", spoke up Nosher Slyfield to his mate Jeff Gleeson, a bony, loose limbed man with a narrow face, both old 2nd Battalion members who had spent the last two years in pursuit of the IRA, "listen to this". Nosher, black hair, broad eyebrows, a darkish skin and built like a boxer, began to quote from a newspaper he purchased for a penny on de-training earlier: "Mister Philip Cosgrave, uncle of the chairman of the Irish Provisional Government was shot dead in a Dublin bar on Sunday night as he fought with four robbers armed with revolvers".

"I'm laugin' in church," snorted Gleeson. "Let's see if they can take it now like they been spooning it out."

Joe Penton wasn't listening. He hunched over the rail, having spied a teenage girl, slim and blond, boarding. She was helping an older woman with two young boys, as RSM Rickman followed, each one clutching an article of baggage. From Penton's overhead vantage, admiring the girl, he surmised this to be the RSM's family and daughter. He was partially correct. The woman was his wife and the boys his sons, but the girl was his niece, Rose.

John

Rickman and his brother, both married, joined the QLI at the outbreak

of war in

August 1914. Part of

His brother died in that tragic blunder called a battle, leaving a wife and young daughter. Then in the influenza epidemic of 1918 the wife was also taken, resulting in Rose's adoption as a claimed dependant. In this manner they had been living as a family for four years. With the Armistice, as a regimental sergeant-major, John Rickman decided it would be more to his advantage to remain in the army but because of others more senior than he with the same intention, he had to drop down in rank, only this year regaining once again the promotion to RSM.

Rose, on finishing her schooling and now at sixteen with no other relations to take her, was accompanying her adopted family into an uncertain service environment on the Indian sub-continent, but the situation did not disturb her, she was looking forward to it with growing relish.

--o0o--

"So

this is

the dreaded

From among the group of men around Sid no reply came, until Jeff Gleeson, sitting on the deck behind, took the unlit pipe from between his lips and began tapping the bowl on one of his rubber pumps.

"You

just

mind your good fortune," he recommended. "In thirteen I came across her

in the

old Astara on my way out to

The 2nd QLI were sailing east 'trooping'; something the nation's soldiers had done since the late seventeenth century and by this time perfected to a smooth drill. Beginning on the 1st of October and ending on the 31st March, thus avoiding travelling and arriving in the hot weather, fleets of ships scurried back and forth, to and from Hong Kong, Singapore, Bombay, Aden, through the Mediterranean, all commencing or terminating at one of Britain's coastal ports.

Unhappily, it was found that they were not to idle the cruise away. There were emergency drills with cork life jackets, and many jobs to do, such as washing up and spud bashing in the galley, cleaning ship for officers' rounds, fire picket, or even standing sentry in dark narrow companionways and hidden little rooms in the deep cramped reaches of the ship. Games were organised: boxing, tug-of-war or physical training, but the slope of the deck made most of these impracticable. For the ship, suffering either a fault in design or a war wound, sailed with a permanent slope, tilting five degrees to starboard.

Mid-journey

for the 2nd QLI's was

Both trading and sport came to an end when the families slipped ashore to shop in the town, while the soldiers filed off for a march. Once gone the crew sealed all ventilation and entrances for refuelling to begin. Throwing open the bunker covers, two gangways were positioned from the wharf, setting in motion a steady single file of ebony black coolies, both men and women. Up one gangway they came with a shallow basket of coal balanced on their heads tipping it down a hopper, before continuing the cycle down the second to collect another.

Returning, the passengers found the ship coated in coal dust and, despite the discomforting heat, having to be sealed in for the remainder of the day and night, for coaling by hand was a long filthy job. The next morning as the ship set off down the 'sweet water', the crew got busy hosing the black film off its superstructure.

Entering

the sweltering heat of the

Already aboard this new transportation were other passengers, who warned the new arrivals not to take up occupation in the cabins, for they were infested with rats.

This,

being

quite true, had most of the passengers living day and night on the

upper decks,

seeking shade on the port side during the sun's hottest periods and

sleeping

anywhere space could be found when it declined at night. Due to the

plague of

rodents, segregation was dispensed with. In the evenings families and

soldiers

gathered, intermingling in securing bed spaces. But before sleep a

cabaret

singsong took place. For music they had a three piece band: accordion,

harmonica and banjo all played by their soldier owners. The women

danced and

the men sang, murdering tune after tune, throats well oiled with Dutch

lager

collected at

On conclusion, to snap everyone out of this maudlinism, Rose Rickman took the stage to sing and dance rag-time tunes even her aunt Harriet didn't know she knew and the men loved it, cheering and joining in the songs.

"We'll be docking tomorrow," commented Jeff Gleeson the next morning to Joe Penton.

"How you tell?" asked Joe quizzically.

"See

them?"

Jeff had taken his empty pipe from between his teeth to point at specks

in the

sky, "Them's swallows. T'evening

they'll

be down here zoomin' around the ship. Them's nest in

CHAPTER 4

If we do not take

care,

People will be

ordered for the

benefit of their health to

On

the day

the shoreline of

"All ashore that's going ashore!"

The

white

coated steward, tapping a bronze gong to emphasize his warning, passed

quickly

along the deck, for being on the river side of the ship there were few

passengers to heed him. The

dockside of

the boat was the focal point of the moment; cheering travellers lined

the

railings throwing paper streamers at parting friends and relatives on

the madly

waving quayside below. One

man taking no

part in this joy and sadness of departure, content instead with the

view of

Black

haired, clean shaven with hazel brown eyes, his height of over six feet

gave

the impression of slimness, an illusion that had cost a number of

opponents on

school and university rugby fields painful bruises. Handsome, at twenty

seven,

his staid maturity advanced others' guesses at his age by three or four

years.

This was not unique to him alone; the war had thrown up an entire breed

of such

men. At university

on the outbreak of

war he had enlisted right away, spending four years on the Western

Front,

finishing with the acting rank of major. The year that followed, like

so many

others scared and wanting to forget, he took off from life: parties;

girls;

late nights, drinking; drinking; drinking. At last, coming to terms

with the

stupidity and death of the previous four years, he resumed his

university

studies. These were in the main centred on

Entering the lounge he took a seat at an empty table. There were plenty of those, for although the ship had started to move, most passengers were still by the railings. At the end of his first whiskey and water this all changed, the room filling with sea travellers, the men in blazers and cravats or plus fours and autumn jackets, the women in tweed or sleeved chiffon dresses.

Two young army officers, both 2nd lieutenants, their faces showing a merry eagerness to sample the full delights of a sea voyage, hovered nearby looking for a free table.

"I say!" "The tables all seem to be full. Would you mind if we shared yours?" asked one politely.

"Not at all," replied Robert, standing to extend his hand.

"Robert Christie, Indian Civil Service".

The

first

officer, introducing himself as Miles Holt-Bate, had blond straight

hair, blue

eyes, and was slightly built with a rosy complexion and bubbly- nature.

Both

men, in their early twenties, were of the same medium height but the

second,

Hugh Durand, was of stronger build. On him, tight black hair matched

dark eyes,

and a wide, youthful but strongly lined face. They, on their way to

Over

drinks

the three men speculated on the type of voyage ahead, on what they

might expect

on arrival, and commenting on the latest news of the day - Mustapha

Kemal's

next military move in

A

half-hour

after getting under way, the

From a table near the bar, a clutch of men, jacketless and tie-less with ruby faces, hailed the woman, one standing to offer his chair: "Emma! Emma!"

Declining with a wave of her umbrella, she instead turned on the nearer three asking: "Gentlemen, may I join you?"

"By all means please do. Your presence will add charm to the table," replied Holt-Bate. All three sprang to their feet, Christie crushing his cigarette in an ashtray.

Removing her gloves she introduced herself as Emma Schofield, shaking hands as each stated his own name. The hand she would not release until her mind had run it through her memory.

"Durand? Durand?" she sifted, "any relation to Brigadier William Durand?"

"Major-General retired, now, and yes, my father," replied Hugh.

"Holt-Bate?"

repeated Emma thinking hard, "You've no connections with

"None whatsoever," grinned the blond officer. "Family's in textiles and filthy rich. I'm escaping east to get away from it all!"

"Christie?" Robert's name was repeated back to him by the woman, whose eyes suddenly became cold with admiration. "Sir Nathaniel Christie, would he be ---?"

"My grandfather," interrupted Christie.

"You have friends aboard?" asked Durand, nodding towards the party of red-faced men as the four made to sit down.

"Those!

Gracious no," dismissed Emma, flipping a hand. "Planters, tea and

indigo from

For

an

hour, until the luncheon gong sounded, the two young officers,

replenishing the

woman's port and lemon, fired questions at her. With good reason, for

Emma

Schofield had spent thirty years in

Mentioning

her husband's death after only five years of marriage, she quickly

hurried on

to tell of the mission's expansion, establishing branches in several

locations

throughout northern

Robert also joined in the dialogue keeping his questions to the woman simple and conversational, for she was known to him, but only as the legend. Her husband had not just died he was ambushed and shot dead one morning while riding on the outskirts of Tank by a young Bhittanni tribesman. Fired up by fanatical mullahs, seeking immortality in the gardens of paradise, he slew this unsuspecting and unarmed Christian infidel. Escaping to his home village the murderer avoided government punishment, but so revered was the doctor for the life healing he had administered, asking no payment, that the tribal jirga actually sat in council debating the forfeit of his life. This was no sham, his life only being spared by an elder brother's offering to stand as guardian over the widow. And there, so far as Christie knew, he was still, sleeping each night at Emma's bedroom door.

Christie

was unaware, as he withheld his knowledge of the woman's history, that

she was

also keeping silent of his. Before the turn of the century she had met

both

Robert's father Charles and his grandfather, then in his late eighties,

and

retired to a garden bungalow on the foothill slopes north of

"So this is the Christie grandson," thought Emma to herself, as she studied Robert's relaxed, handsome face whenever he took up the conversation with his pleasant, assured manner. As she watched him she wondered if he knew the story of his grandfather's and father's involvement in the Sepoy Mutiny sixty five years earlier and of how near it had come for him to have never existed. In any normal period of time it would have been classed as a remarkable story, but coming out of that bloody upheaval called the Indian Mutiny it ranked as just another tale from the rebellion. "Yes, he must know," decided Emma, "he must know…"

--o0o--

Nathaniel

Christie, picking up a Wesson Levatt pistol from the bedroom dresser,

checked

the rounds in its cylinder drum before pushing it out of sight in his

trouser

waistband under his white, lightweight frock-coat. It was May 1857 and

the district

magistrate was just off to his courthouse for the morning session. The

time

approaching

Coming

to

Their

destination, Nathaniel's posting was Mauna, a town one hundred miles

west of

Carrying

a

pistol to his work was a habit adopted just in the last week, since for

several

days, wild bazaar rumours had been spreading of rebellion and massacre

among

stations north and along the Ganges's basin, down to the gates of

This was, sadly, a confidence to be proved wrong. In previous decades the soldier sepoy of John Company's army had a high standing in his village. Now through a number of unwise government legislations this was unwittingly being eroded. There were also unfounded tales of soon having to become Christians, allowances being reduced when serving away from home provinces, of being transported across the black water sea, destroying their caste, and the one that really inflamed fears, pig and cow fat was being used in the manufacture of the new greased rifle cartridge shortly to be issued. Of this last, the recipe had not altered. A mixture of beeswax and linseed oil. But how to prove that to a man in deadly fear of his caste being violated?

Also

about

the land was a populace bent on stirring unrest and feeding the sepoys'

misgivings. The English had been beaten by the Afghans fifteen years

earlier

and in the Crimean War, only just ended, they swore that the British

Army was

all but wiped out. The time of the white faces in

Also

unknown to him, rebellion and massacre was rampant in

Cantering to the end of the dirt surfaced Mall, Christie turned into a street that was the British Raj's authoritative administrative centre of the town. Along the Mall he noted the scarcity of native workers, cantonment-employed grounds men and sweepers for clearing away the cow dung. Approaching his court building, the emptiness of this area now gave an air of unease. At this time on any session day the street outside would be filled with up to a hundred people, witnesses for cases of criminal acts and petty misdemeanour and petitioners and their witnesses seeking settlement of a dispute. Today though, the magistrate's eyes took in only one person across the street, the town postal clerk, a retired British army sergeant, married to a Hindu woman, who stood bewildered in his office doorway. Even at the gaol building next to the court there was no life, which was worrying, for a jailer normally stood guard in the shade of its veranda.

With a wave of his riding crop to the postal clerk, who acknowledged with a jerky lift of one arm, the magistrate guided his horse to the back of the courthouse where he dismounted. Usually, before Khan halted, two grooms were on hand to lead him into the open thatched roofed stable but today Christie had to tie his own horse. The court building he found for the first time silently vacant, only high in the eaves was there any sound: sparrows chirping and darting, not yet subdued by the day's advancing heat. On entering, his Indian court clerk, sitting stiffly at his desk, rose to his feet, a courtesy he never failed to extend to his magistrate.

"It appears there is a festive holiday I am not aware of". Christie's comment to his clerk was intended to make light of this strange state of affairs.

An elderly man, the clerk responded in a grave tone.

"There is no festival, Magistrate Sahib. The people are frightened, there is to be trouble - bloodshed."

"Nonsense, Subhash" dismissed Christie, "from whom? Why?"

"You must leave, sahib," stated the clerk without giving a reply to Christie's questions, "All white faces are to die".

"Subhash, it seems you and the town have been taken in by this outlandish bazaar gup.

We are in no danger here; the Army is too near to hand".

Hoping this would reassure his clerk, Christie turned to walk to the front of the court building but was halted and forced to turn about by the clerk's chilling reply.

"I have worked for Government for forty years, fifteen years as babu in this court. I too am in danger by coming to the Raj's court. Perhaps my death here will spare my family. Go, Magistrate Sahib, take your wife and children. Run! Hide!"

Christie marched quickly outside, the street still deserted. He hurried to the gaol. There he could find no-one, the jailers gone, and all cell doors flung open. Then clearly from the direction of the infantry lines ragged musket firing sounded. Rushing to the door he still found the street empty, and then in a moment a lone rider galloped into sight from the direction of the shooting. Seeing Christie, now in the street, he violently reined his horse to a halt. It was Major Francis, the second-in-command of the native infantry regiment, hatless, in his right had a blood streaked sabre.

"Get to the cantonment, Mister Christie!" he shouted. "The sepoys have risen. Heathen scum butchered the Colonel had to cut my way out - warn everyone. I'm going to the cavalry lines - if Stewart's squadron remains loyal we stand a chance. If not - we're all for damnation!"

Minutes later with Khan at full gallop up the Mall, passing fleeing terror-stricken servants, Christie saw horsemen racing away. The yellow coats of the riders identifying them as belonging to the irregular cavalry. At his bungalow he hauled Khan to a halt, leaping down to rush across to a near naked body laying in the carriage drive.

"Agnes! Agnes!" he cried, flinging himself to his knees, clutching at his wife's lifeless form. Her face, body and limbs lacerated with sword cuts, she, first repeatedly raped, had been run through the heart and her stomach cut open before being dragged from the bungalow.

Horror-stricken, he wailed, tears of grief running from his eyes. Then leaping up he frantically rushed into the house in search or his children. Everything that could be was smashed or broken, the baby cot empty, but the framework cut to pieces, the bed clothes smeared with blood. The two eldest children he found outside the back garden playhouse he had built for them. On being discovered hiding there, they had been dragged out whimpering then dismembered with sabre slashes. Shrieking with hysterical anguish he collapsed to the ground, his mind crippled with grief. In this manner he remained until the nearby sound of musket fire triggered a screaming hunger for revenge. Charging to his gateway, pistol in hand, he saw an open carriage thundering towards him driven by a retired major. In the back his elderly wife comforted another woman in her arms, her clothes bloodied.

"Nathaniel!" screamed the major, "your family - run man! Run!"

"They're dead! They're dead!" screamed back Christie. "Into the carriage man, quickly - we must bolt. It's cut and run or die", the major beseeched Christie, clear as to their only hope of survival.

"No! No! I'll not leave them," cried Christie.

"Then I'll leave you to God or the devil, for you'll see one or the other this day".

With that the major departed, whipping his team into a gallop.

In moments another rider thundered into view from the town. He too reined to a halt.

"Nat! The native troops are everywhere, burning and slaughtering. Get your family and flee, the only hope is to take flight". This was Lieutenant Hancock, a detached officer on settlement survey duty.

"Dead! They're dead!" said Christie through clenched teeth. Then seeing a ragged body of red coated men spill into the Mall, he, aiming his pistol, advanced towards them. Firing his rounds away he stood awaiting the musket armed mutineers' reappearance from cover, prepared to die fighting bare handed.

"Mount, Nat! Mount! You'll not gain revenge at these odds."

At his side he suddenly found Khan, his reins held by Hancock.

Climbing into the saddle the two men raced away from Mauna, firing still to be heard, slender shafts of smoke from burning bungalows snaking skywards.

Throughout

the next six months, with the world stunned by the reports of mass

butchery of

the white population of Bengal and elsewhere, the few British troops

and those native

sepoys remaining loyal, spread along the

During this interim period Nathaniel Christie, with no other thought but that of revenge, threw his lot in with a group of men who formed a band of moss-troopers. They, like he, were made redundant by the rebellion, many also like him with scores to settle. Officers of mutineered regiments, white merchants, government teachers, church clerks, loyal Indian officers and sepoys raging to redeem the shame brought upon their regiments, railway officials and telegraph operators, all falling in together as a bush militia. Mounted on whatever horses were available their weapons were an assortment of carbines, sabres, shotguns, lances, pistols, whatever could be acquired which suited the individual. Christie armed himself with his pistol and a hog spear, a hunting tool that proved most effective in slaying men from horseback.

Forty

three

troopers, they patrolled through the summer and monsoon months in the

saddle every

day. The warrant given them: to keep the byways south of the

There they would be tried by an army court-martial and if found guilty of being a mutineer or plundering the land, they would be hanged, or in most instances, blown from a gun. With backs to the muzzle the native's arms would be lashed by ropes secured to the wheels. On the firing of the powder charge, the torso would disintegrate, legs sagging to the ground, arms flying away on their ropes, the head always popping in the air like a cork.

Action for Christie's band was at times furious and deadly, but only in small ways. A sighting sparked breakneck pursuits across dusty plains or rain flooded jungle trails, ending in capture, or if their quarry turned to fight, wounds and deaths. Their first major engagement in which substantial casualties were suffered occurred on a moist morning at a remote village beside a cart track twenty miles east of Banda.

Into the arms of their night picket staggered a young Muslim cultivator, bare foot, turban-less, with just a loin cloth for covering, his back wounded by a sword cut. Incoherent with terror, the one grain of fact learned from his babbling was that his village appeared to have undergone an attack. Minutes later, the farmer's wound having been bandaged; he was taken along riding up behind one of the troopers. Tracking south, the horsemen rode for the first five miles at a canter before slowing to a trot. Then on coming upon corpses on the cart-track the pace slowed to a walk. As the dead became more frequent the guide began to talk loudly, indicating he was afraid to go on. Therefore, being of no further use, he was pushed from his mount's hindquarters. It was becoming light and on emerging from a thick forest a village of mud walled huts came into view.

Captain Hobday, who had narrowly escaped with his life from Jhansi when the 14th Cavalry turned against their officers, and who was now their agreed commander, halted the troop of horses. Perhaps half a mile distant, the village was surrounded by crop fields, root vegetables and barley. Crisscrossing the fields were narrow irrigation ditches fed from an earth banked water tank to the north of the village. This itself comprised about forty huts with a number of pens and straw roofed pole frameworks for sheltering stock. Hobday, to await better light and yet maintain the cover of the remaining darkness, led off around the edge of the forest to the western side of the fields. Even here they passed bodies: men, old women and children, evidently caught before reaching the forest's shelter. Hushed, they made their way, the only sound, the creak of leather and light jingle of saddlery metal.

Formed into a single line the troopers sat facing the village and the whisper of morning light beyond. With no proof that the raiders of the village were still present, Hobday was not prepared to enter it until confirmation one way or the other was forthcoming. Motionless, they sat listening to the forest around them awaken: a jungle cock, a peafowl and the howl of a jackal disturbed from feasting on a corpse. But from the village no sound, which was uncommon, for at this hour the village pariah dogs should have been calling to each other.

Deciding it was no longer safe to wait, since the morning light would soon uncover their presence, Captain Hobday nudged his horse into a walk. On that signal the whole rank moved with him. Having covered a third of the distance to the hutment, somewhere in the village a horse neighed, to be answered by one of their own green mounts. At that, caution was discarded, horses spurred to a canter, trotting across the crop fields and over irrigation ditches. Swinging around a tall clump of bamboo, Christie could see the village layout clearly before him. Surrounding the ashes of fires from the night before, clusters of men lay asleep, until one, on hearing the thudding of a horse's hooves on a hard earth pathway, leaped up to shout a warning. They, in tattered uniforms, were a body of renegade mutineers taken to pillaging, who, after attacking and butchering the village, had remained to rape the women and drink darro, the village alcoholic brew.

Awakening to find charging horsemen all but upon them, they either ran or stood. One, before Christie, held up a musket with a bayonet sword ready. The magistrate brought his spear down and with Khan at a dead run, he leaned low over his horse's neck letting the point drop. In a blink the native soldier, with a cry, vanished below Khan's hooves, Christie sweeping his spear up behind to recover, aiming forward, the point blooded. Again he used it this time into the back of a red coated figure running between two huts. Then again into the back of someone trying to reach the cover of a patch of sugar cane. Turning his horse he galloped back into the village to find single combat taking place everywhere.

Mutineers asleep in the huts were spilling out into the earthen yards with weapons in hand. One trooper stood dismounted at a doorway sabring all who came out. Another left his horse to hunt in the darkness of a hut with his shotgun. Christie rode to the assistance of a railway plate man, on horse, but surrounded by mutineers. Dragged down, he was bayoneted repeatedly, Christie, reining his horse, fired his pistol into the group, despatching them or driving them off. Then again he raced through the village, spearing, and out into the field, riding down as many of those he could before they reached the forest's edge.

Of

the